With the popularity of the ketogenic (keto) diet these days and the amazing results people are reporting, my clients have been asking whether the ketogenic diet is right for their child with autism.

I have been looking for good science that can guide us as to whether the ketogenic diet improves the symptoms of autism. And how it compares to other diets, and which diet is best.

And I have found the science!

In this 6-month study, Egyptian researchers compared the effects of two different dietary interventions versus a normal (control) diet on core symptoms of autism. Although more research is needed, findings from this study are promising.

How the study was conducted

The study population consisted of 45 children – 33 boys and 12 girls – aged between 3 and 8. Two senior psychologists specializing in the diagnosis and management of children with ASD confirmed the participants’ diagnosis of autism using the DSM-5 criteria.

The researchers assessed the following:

- Anthropometric measurements such as weight, height, and head circumference

- ASD symptom severity using the “Childhood Autism Rating Scale” (CARS) once at the beginning of the study, before implementing any dietary changes and again after 6 months. The higher the score the more severe the autism symptoms.

- Treatment efficacy using the “Autism Treatment Evaluation Test” (ATEC) questionnaire before starting the diet and 6 months later. As with the CARS test, the higher the ATEC score the more severe the autism.

- Fasting lipid profile, liver function tests, complete blood count, and fasting blood sugar levels

- Urinary ketones and random blood sugar levels were checked weekly

The children were randomly assigned to three groups:

- Group 1 received the ketogenic diet as the Modified Atkins Diet (MAD). The MAD was used in this study to make the ketogenic diet less restricting for the children and account for their growth requirements.

The original ketogenic diet consists of 80% dietary fat (mostly from long-chain triglycerides), 15% protein, and 5% carbohydrates.

The MAD used in this study consisted of 60% fat, 30% proteins, and 10% carbohydrates. Carbohydrates were restricted to 8 to 10g per day based on the patients’ age and weight.

A team of expert dietitians explained the principles of MAD to the 15 children’s parents. The parents were also taught how to:

(i) Prepare meals at home by following meal plans designed by the dietitians

(ii) Count dietary carbohydrates

(iii) Measure urine ketones at home using the ketostix

(iv) Detect signs and symptoms of ketosis and hypoglycemia

- Group 2 received a gluten-free, casein-free diet. The 15 children in this group were asked to avoid the proteins casein (found in all milk and derived products) and gluten (found in wheat, barley, rye, and some types of oats).

The dietitians taught the parents how to:

(i) Create and maintain the GFCF diet by following meal plans

(ii) Read food labels

(iii) Complete 24-hour food recalls

- Group 3, the control group, received balanced nutrition. The remaining 15 children weren’t on any type of diet therapy and allowed to eat at their own preferences. Their parents were explained how to provide balanced diets to their children during one session with the dietitians.

What the researchers found

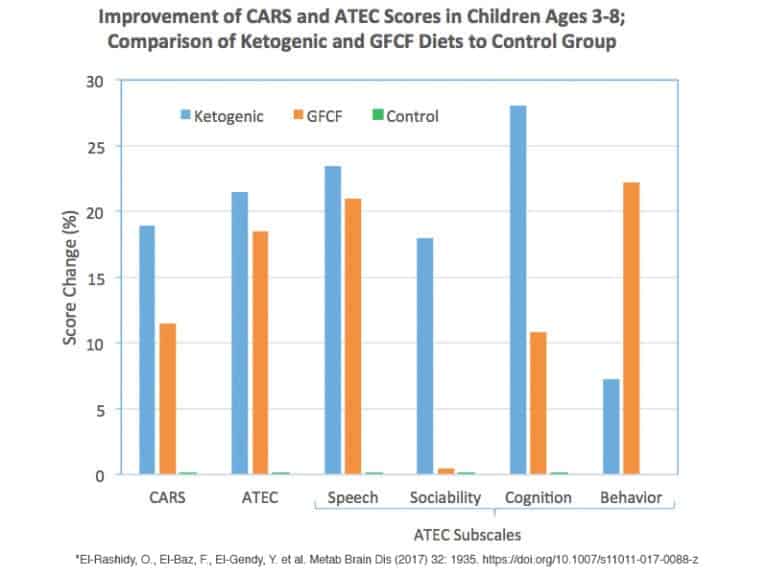

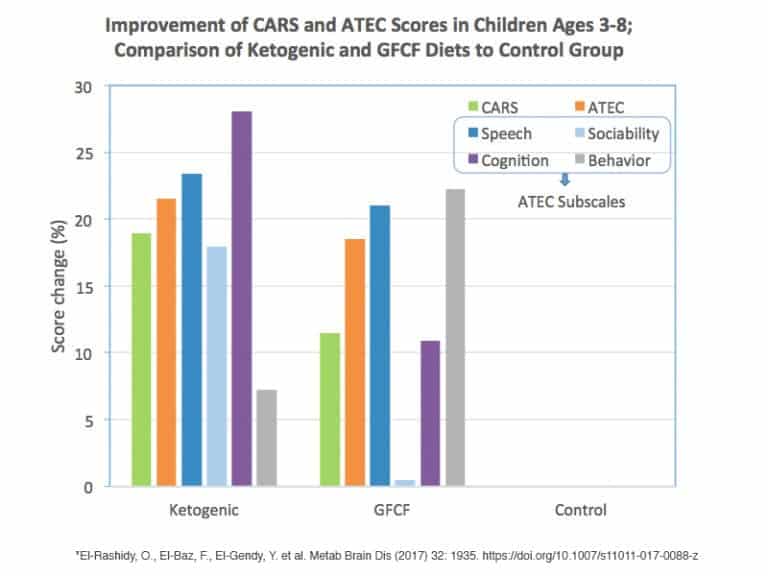

Keto Group

Five of the fifteen children (33%) in the Keto/MAD group dropped out of the study due to poor compliance to the diet (vs. 0 % dropped out in the GFCF group).

The remaining 10 children in the Keto group showed significant improvements in their:

- Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) scores

- Total ATEC scores, as well as ATEC scores for speech, sociability and cognitive awareness.

Behavioral problems in this group decreased but no statistically significant changes were observed.

GFCF Group

All children in the GFCF group compiled with the diet. In the GFCF group, children showed significant improvements in:

- Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) scores

- Total ATEC scores, and ATEC scores for speech and behavior improved.

Participants showed improvements sensory/cognitive awareness but they were not statistically significant.

The Keto group showed more improvements in terms of CARS and ATEC scores, compared to the GFCF diet group.

No significant changes were seen in the control group.

Charting the Results

After I plugged the data into a spreadsheet, the results became more clear to me. The following charts compare the results of Keto, GFCF and the control group. Notice how both the GFCF and Keto group have significant improvements compared to the control group (that did not do a special diet). There were some differences, but overall the results show that a special diet is very helpful to improving autism symptoms.

What the findings mean

So what do we do with this data. This is MY interpretation of the findings. (This is not the study author’s opinion.)

- Autism severity decreased among children in groups 1 and 2 indicating that the Keto and GFCF diet were effective in improving autism symptoms.

- The ketogenic diet yielded better results than the GFCF diet. The ketogenic diet can be a great diet for autism… for the right person. The keto diet can address some underlying mitochondrial issues and neuroinflammation that can be wonderful!! By improving the underlying biochemistry, the symptoms of autism can be significantly reduced (as we saw in the study).

- However, 1/3 of the children dropped out of the Keto group. The fact that the keto diet is more restrictive is one of its challenges. If a child goes on keto, but the family stops because it’s too difficult to maintain (no judgement), then the child doesn’t receive any of the results that were seen in the study. (Unless they transition to a different diet.) No one dropped out of the GFCF group and great benefits were seen by that group too. In this case, the “best” diet is the one the family can do, that yields positive results. For some it’s keto, for some it’s GFCF.

- Since results were better on the ketogenic diet, this might lead people to think the ketogenic diet is the best place to start or the best diet for everyone. It might be, especially if you have reasons to think that approach would address underlying biochemical problems and be a better diet. As I mentioned, the keto diet can address metabolic issues and neuroinflammation and be very helpful. However, the ketogenic diet has some challenges and deficiencies that can result. I have seen children with autism do really well on the ketogenic diet, and other children do poorly on the ketogenic diet. Although, for the right people, most are negatives are outweighed by the benefit of keto or can be overcome with diet hacks. More study will help us determine the reasons the ketogenic diet was helpful and if the benefits continue for long term. The choice is a bioindividual one.

- Why did keto help people? The study did not isolate why the ketogenic diet worked better. The keto diet removes: gluten, grains, starches, and other compounds in foods that can be irritating to the system. So, if keto is showing improvement, we don’t know what caused the improvement. It might be the 1) removal of gluten, 2) the removal of grains and starches, 3) “lower” carbs (but not ketosis), 4) a decrease in total sugar (or some other compound like FODMAPs, oxalates or salicylates) that was reduced that was the key to the diet’s success. Graduating the food removal from simple to more restrictive is a good way to see WHAT about the diet was helping. This leads me to #6…

- In my clinical experience, if someone is transitioning from the Standard American Diet, it might be easier and better to start with a GFCF diet. It’s an easier diet and lifestyle choice (if it’s effective), and can eliminate some of the most common reactions: gluten and casein. Going step by step can help determine which diet is ideal. It’s helpful to start with gluten and casein, then eliminate all grains and starches to see if the issue are foods that irritate the gut (i.e. grains and starches), then proceed to the ketogenic diet. While it is true that some people can jump right into the ketogenic diet, gradually decreasing the amount of carbohydrates consumed with a grain-free diet first can help the body adapt to a lower carbohydrate diet before starting the ketogenic diet. And since we don’t know exactly what it is that’s contributing to the improvements on a ketogenic diet, taking it step by step, helps someone figure out how far they need to restrict their diet, and help them understand the reason they are benefiting from the diet change.

- Diet support. This study shows us that having access to foods that meet the specifications of the dietary regimen can improve compliance. In this study, participants in groups 1 and 2 had access to a specialized kitchen that provided group 1 children with low carbohydrate biscuits, cakes, and bread and group 2 children with alternatives to gluten and casein. Having support with ready-made meals, or even building into your schedule to prepare the meals, can help increase your success. For instance, Seek out help when doing a special diet if you need the extra support. Even though some people dropped out of the study, from my experience they had very good compliance. And I believe part of the success was this diet support.

- Individuals with autism have impaired gut function and various nutrient deficiencies which can slow down gut healing and how quickly you see results. As such, someone with ASD may require several months of dietary intervention before seeing significant symptom improvement. Remember, this study was 6 months. You often need to give dietary intervention some time to see what improvements unfold.

Conclusion

This research is further proof that a special diet helps people with autism. And it shows: both a GFCF diet and a keto diet were effective.

I hope this study helped you see how ketogenic can be a wonderful option for certain children with autism. And further proof that a GFCF diet is very helpful.

It’s an exciting time (as always) in the field of nutrition.

Reference:

El-Rashidy, O., El-Baz, F., El-Gendy, Y., Khalaf, R., Reda, D., & Saad, K. (2017). Ketogenic diet versus gluten free casein free diet in autistic children: a case-control study. Metabolic brain disease, 32(6), 1935-1941.