Most thriving nutrition practitioners have a few “secret tools” and strategies that get them results, even for some of the most “difficult cases.”

Throughout my 18+ years as a nutrition professional working with complex neurological and physiological conditions, this one nutritional strategy has repeatedly triggered breakthrough results… Assessing oxalate levels.

This approach is something that most practitioners are unaware of today; but as YOU learn this one key principle and approach and put it to work for your clients, your practice will thrive too.

I have written extensively on this topic so you may already have some background on oxalates. They are a natural food compound which are found in very high amounts in foods considered “healthy” such as almonds and almond flour, beans, soy, quinoa, dark chocolate, green tea, turmeric, and a list of fruits and vegetables including spinach, swiss chard, beets, celery, carrots, sweet potatoes, raspberries, kiwi, and pomegranate.

A fair number of your clients may have issues breaking down oxalates in their food. Oxalates can cause a host of problems when a person is not able to properly eliminate them, and they build up in tissues, organs, and joints. Some issues are very serious because they cause oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage. And this can cause problems in any system of the body, be it: digestive, neurological, immune, pain-related disorders, and many chronic diseases.

Oxalates can be the cause of the disease or a contributing factor.

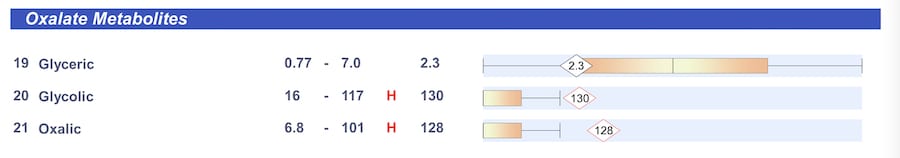

If your patient’s oxalic acid marker is high as measured by the urinary OAT lab test (the image featured below is from The Great Plains Laboratory version), you can infer they likely have high levels of oxalate in their body, and may have built up to harmful levels that cause damage and a host of primary symptoms.

I teach practitioners that you can have a normal (not high) organic acid marker (like my colleague Trudy Scott had), and actually still have a problem with high oxalate levels in the body. And subsequently a low oxalate diet may be needed.

You may be a nutrition practitioner who cannot or does not wish to use lab testing…

So how can you determine if the low oxalate diet would benefit your client?

Well, you need to look at multiple factors to truly determine dietary direction.

Within step 5 of my 6 Pillars of BioIndividual Nutrition, one of the things I use to Customize BioIndividual Nutrition Strategy are the steps needed to determine diet direction.

You need to consider all of these options before create a plan, and that requires consideration of multiple factors, laboratory testing being one of them.

The factors I teach in my BioIndividual Nutrition Training program include:

- Food cravings

- Diet record, food frequency

- Reactions to foods

- Common symptoms

- Laboratory testing

- Genetics

- Client considerations

BioIndividual Nutrition practitioners consider the whole picture when making dietary recommendations. When I look at it from every angle/factor I can paint a more accurate picture of what’s going on. And the best way for me to do that, is to see if several of the above factors are consistent.

Laboratory testing is one piece of the puzzle. When I suspect a client has problems with oxalates, yet their organic acid testing showed “normal,” I would consider all of the factors above to determine if the low oxalate diet was a reasonable strategy.

- I’d look at their diet record to understand the frequency/quantity of their consumption of high oxalate foods such as nuts, almond flour, beans, potatoes, sweet potatoes, chocolate, beets, spinach, and other leafy greens.

- I’d investigate any existing reactions to oxalate foods. Have they already noticed some reaction to them?

- I’d ask and see if my client’s symptoms were consistent with high oxalates such as: fatigue, pain, burning feet, urinary urgency or frequency, anxiety, vulvodynia, kidney stones, pain in the eyes, and others.

- I’d be curious – do they have any genetic polymorphisms or poorly functioning biochemical pathways that might shed further light on whether oxalates could be an issue? For example, could they have pyroluria (like many mental health patients) and be low in Vitamin B6? We know endogenous oxalate (oxalate internally manufactured) can be caused by low B6. So to best serve my client, I consider these important factors.

So when you are making a determination on your next dietary direction, be sure to keep oxalates in mind, as well as all of the contributing factors in order to save you extra time by avoiding trial and error.

If you’d like to learn all of the ins and outs of the low oxalate diet without years of trial and error, join us for the BioIndividual Nutrition Training, discounted winter enrollment is underway now.

Knowing and applying ONE key principle can significantly improve your practice.

Professionals are joining the program from around the world, I hope you will join us.

Julie