Diet influences the intestinal tract, gut microbiome, and brain.

And personalized nutrition, or BioIndividual Nutrition®, can have a profound impact on the mood, learning, and behavior (i.e. the brain) of our clients and patients.

In fact, clinicians in my BioIndividual Nutrition Institute have been successfully using nutrition to help support their clients with mental health conditions, long-thought to be purely “in their head.” We now know that it is not just in our clients’ heads but in their guts and even their immune systems. That means we (nutrition professionals) have incredible value to bring in terms of benefits seen when the right nutritional intervention is employed.

I recently read a new study, Role of diet and its effects on the gut microbiome in the pathophysiology of mental disorders, by Horn et al.[1] which reaffirmed and/or further cemented the role that dietary intervention plays on the microbiome, and therefore the brain, in mental disorders.

As a nutrition consultant that works with children with mental health conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, and autism, I wanted to share some highlights (the article has over 130 scientific references!) I thought you might find most interesting and helpful in your practice as well.

What is the Brain-Gut-Microbiome (BGM)?

Let’s start with the relationship between the brain, our intestinal tract, and gut microbiota.

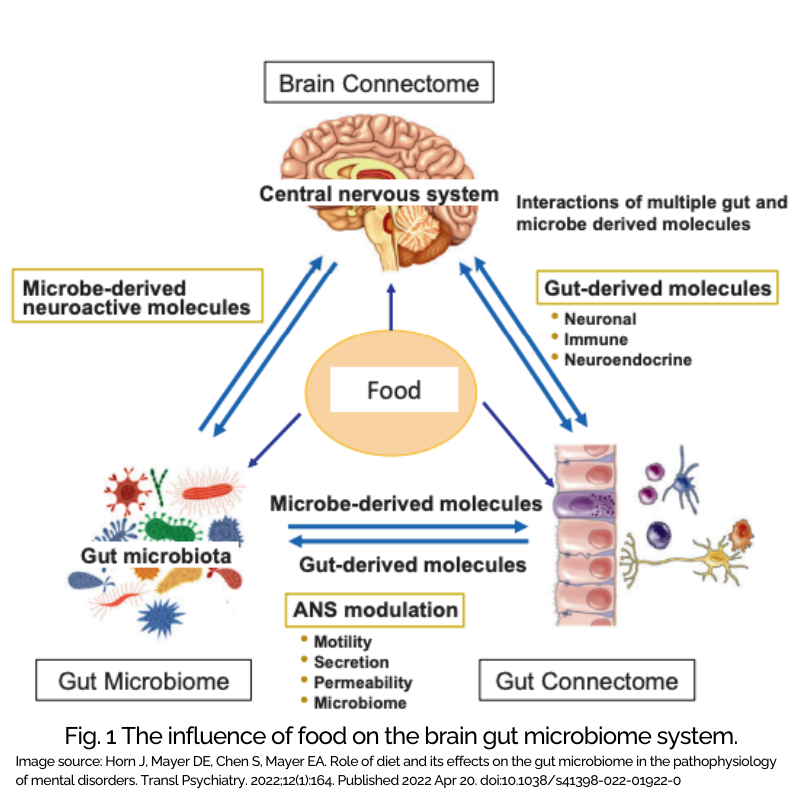

In their article, Horn et al. begin by referencing the BGM – brain-gut-microbiome system and discuss the ways diet modulates it!

Isn’t this exciting! Haha. The nerd in me loves to see these connections and the studies to back them up… and have it align with what I’ve seen in practice and in the experience of my clients for so many years.

The BGM is made of several systems in the body including the neuroendocrine, neural, and immune communication channels. As I pointed out before in my article on the two-way relationship of the microbiome and diet, there is feedback between these systems and diet not only helps to shape the microbiome but it can also impact the structure and function of the brain because of this bi-directional influence.

Figure 1 from the study by Horn et al. illustrates this system so well. Food affects our brain, gut microbiome, and intestinal tract AND each organ (yes, some are researching the microbiome as the last human organ) interacts with each other in a two way street.

This complete communication system means that the food we eat can affect our brain and so much more.

So how can diet have this big of an impact on the brain? Let’s go through the crucial points.

Diet Impacts the Brain in Multiple Ways

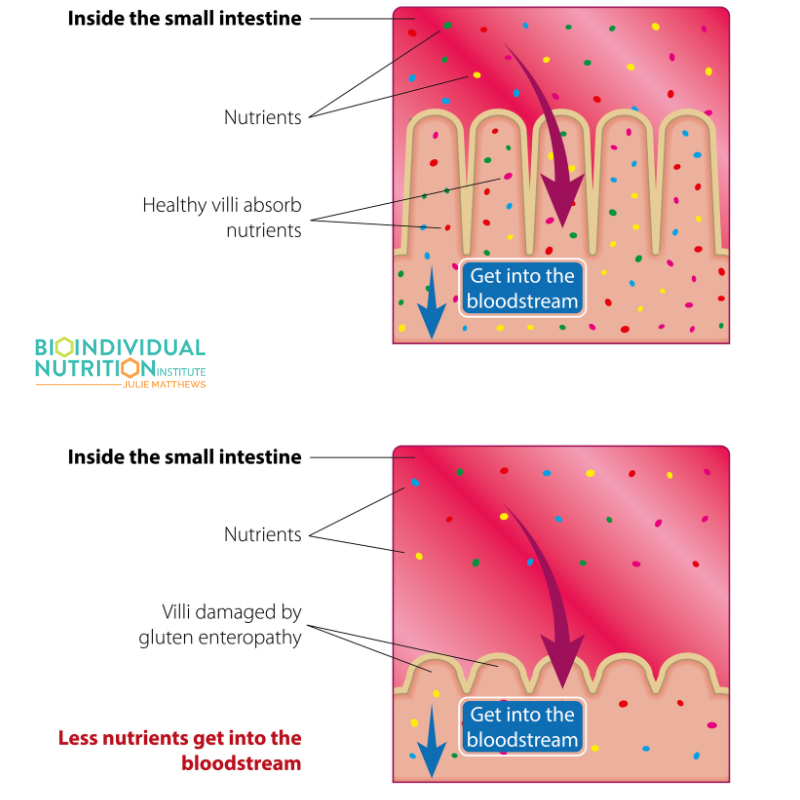

What is well known is the role of macro and micronutrients for optimal brain development and how these nutrients, when deficient, can result in poor brain function. However, the predominant focus has been on specific nutrients with direct absorption in the small intestines.

What is well known is the role of macro and micronutrients for optimal brain development and how these nutrients, when deficient, can result in poor brain function. However, the predominant focus has been on specific nutrients with direct absorption in the small intestines.

Now, there is more awareness about the role of the microbiome and the metabolism of food molecules by our microbiota.

It is not just what we eat and absorb but also what our gut bugs process as well.

Depression

Diet impacts depression in a myriad of ways. First, an altered microbiome has been found in subjects with depression as compared to healthy controls without depression. Next, an unhealthy diet has been shown to result in poorer mental health outcomes in children and adolescents.

Systemic immune activation has also been studied in relation to depression and specifically associated with diets leading to metabolic endotoxemia such as the Standard American Diet (SAD).

And then Horn et al. referenced the SMILES trial which was an intervention study that found that dietary intervention caused a statistically significant decrease of depression when compared to conventional therapy by itself. Interestingly as well, there was a study that looked at dietary intervention that included a decreased ratio of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids which resulted in reduced self-reported depression.

Anxiety

Standalone anxiety is at an all-time high, in adults as well as children. But, anxiety is also a common comorbid condition in things like Alzheimer’s, autism, and depression.

So understanding the nutritional underpinnings, nutrient considerations, or biomedical therapies that can improve anxiety is critical. There have been connections made between dysregulation of the microglia (immune cells in the brain) along with gut dysbiosis and anxiety. Addressing overall gut health, supporting a healthy microbiome, and addressing pathogens can be effective.

In terms of nutrients, omega-3 fatty acids are inversely related to anxiety which brings in potential for nutritional considerations that bolster the essential fats in the person’s diet.

ADHD

This is a condition where I have had concerted focus in my own clinical practice and have seen tremendous potential and improvements. This article by Horn et al. looked at two studies in terms of nutritional intervention and ADHD.

The first was a study of 100 children randomly assigned to either the dietary or the control group. They applied an elimination diet to the dietary group and compared the two groups using the ADHD rating scale (ARS). They showed significant improvement in the dietary group which followed the elimination diet.

The second study Horn et al. referenced assessed microbiome differences between individuals with ADHD and those without. They found a nominal increase in one species, but using a hypothesis-driven approach, they determined something quite interesting. That increase in gut bacteria was linked to an enzyme which is involved in the synthesis of phenylalanine. Phenylalanine is important here because it is a precursor of dopamine. The results showed that individuals with ADHD had certain increases in gut microbiome which predicted function of dopamine precursor synthesis and decreased neural responses to reward anticipation. One criteria for ADHD is decreased neural reward anticipation.

Autism

This is an area of special focus for me, as many of you know, as I participated in a study looking at therapeutic diets as well as nutritional supplementation in autism.

With the high rates of comorbid conditions in autism related to the gut such as constipation, GI distress and pain, reflux, diarrhea, food intolerances, picky eating, and dysbiosis, it is not hard to put together the intricate relationship between the gut and the brain with this condition.

Between the study I participated in as well as others in this space, what is clear is that personalized therapeutic nutrition intervention helps whether due to reducing inflammation, boosting nutrition, shifting the microbiome, or all of the above.

There has also been work in the space of Microbial Transfer Therapy (MTT) which is where fecal matter from a donor is transplanted into the individual with a disrupted microbiome.

The improvements seen indicate that autism (as with other conditions) is impacted by the microbiome and using nutrition can be beneficial in supporting changes in the brain as well as the gut.

Epilepsy

This condition, and more specifically drug-resistant epilepsy, has been long-studied in relation to a specific nutritional intervention, the Ketogenic Diet. While all of the mechanisms have not yet been fully understood, intestinal dysbiosis has been implicated and when adjusting the diet to reduce carbohydrates and boost fat, a change in the microbiome happens which positively benefits seizure activity

Eating disorders

Interestingly there is some data on the role of specific dietary intervention as it relates to eating disorders such as binge eating, bulimia, and anorexia. Again, the studies that Horn et al. reference show certain variances in the microbiome. In fact, there were significant differences in certain strains of microbiota in individuals with anorexia compared to those without.

And, two additional studies they reference showed how nutritional intervention can be effective, specifically focusing on a Mediterranean diet. One of those studies referenced involved over 1400 subjects deemed “high risk” for binge eating. When they had strict adherence to a Mediterranean diet, there was decreased development of binge eating. The other study had an impressive number of almost 12,000 women with anorexia or bulimia and that showed an inverse association between a Mediterranean diet and those eating disorders. This has exciting potential for treatment in previously hard-to-treat conditions.

Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease

More data is known on the role of effects of early nutrition on developing brains. But, now there is increasing focus on the role of chronic dietary choices on the brain as we age and more specifically the impact it may have on cognitive decline and conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Neuroinflammation as a result of microbiome composition has been shown to be a precursor to cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s.

How Diet Improvements Support a Healthy Brain

In their study, Horn et al. identify three ways that diet aids brain structure and function. These include reducing endotoxemia, the impact of neurotransmitters, and the importance of micronutrients. Here is more on each of these factors.

Reducing Toxicity from the Standard American Diet (SAD)

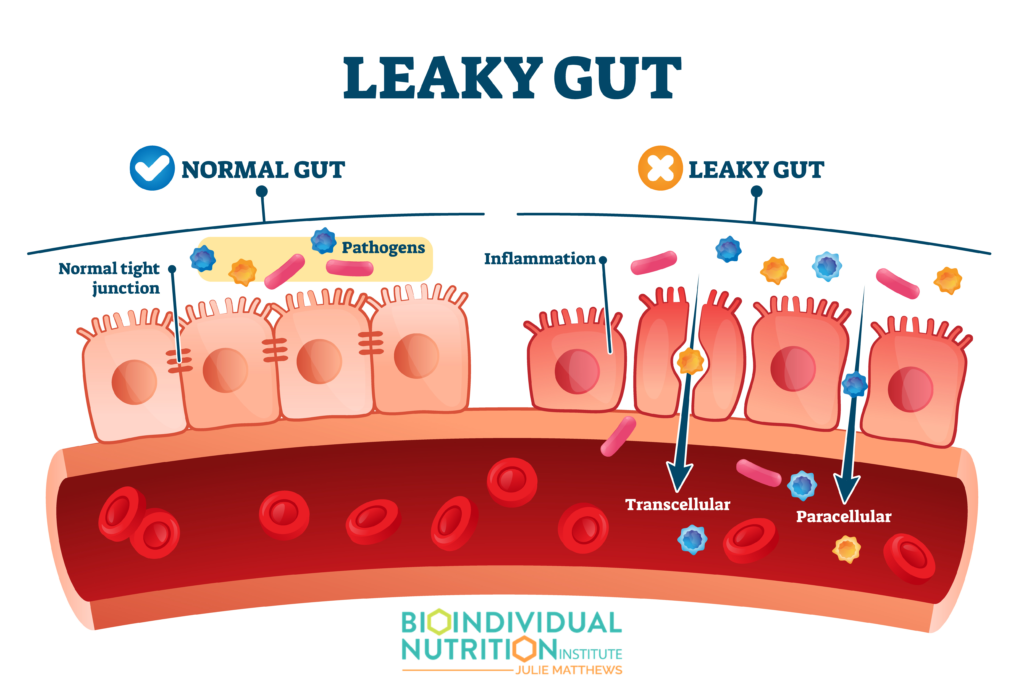

A Standard American Diet (SAD) has sadly been connected with something called metabolic endotoxemia where the gut barrier becomes compromised. This is also referred to as “Leaky Gut” and is linked to systemic immune activation.

A Standard American Diet (SAD) has sadly been connected with something called metabolic endotoxemia where the gut barrier becomes compromised. This is also referred to as “Leaky Gut” and is linked to systemic immune activation.

The good news is that changes in diet can mean a reduction in endotoxemia through microbial composition changes.

Increasing microbes with anti-inflammatory actions can be accomplished through a personalized diet with prebiotic foods or supplements. This can provide food for the good gut bugs and help increase the microbiota associated with the metabolism of carbohydrates into short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). A SAD usually does not contain a rich variety of whole foods which support the microdiversity of the gut bacteria leading to downstream changes in the gut lining and integrity.

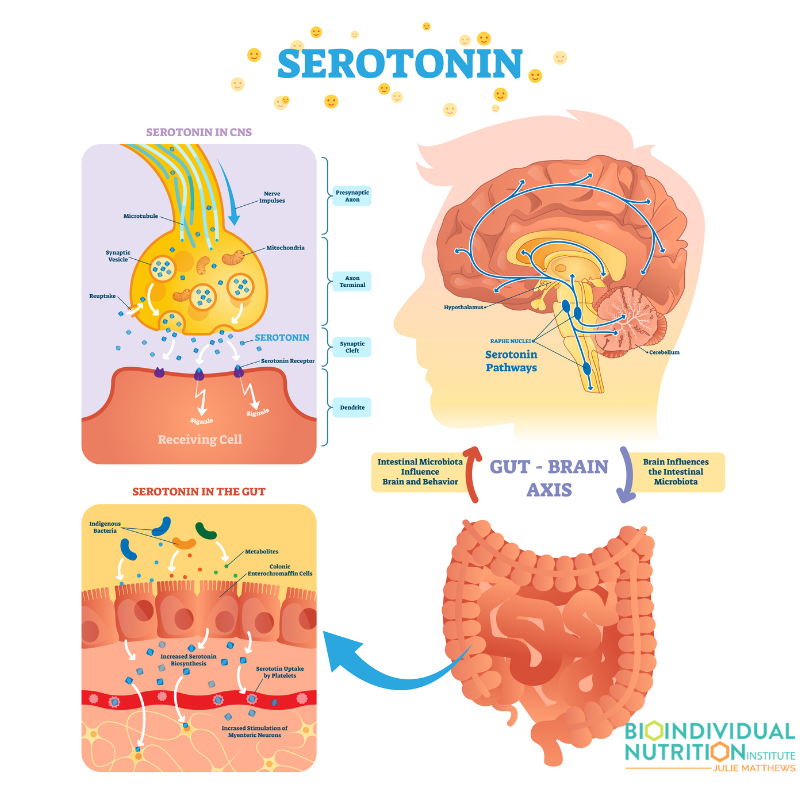

The Impact of Diet on Neurotransmitters

95% of the body’s serotonin is produced and stored in something called enteroendocrine and enterochromaffin cells or ECCs. These ECCs are integral in modulation of brain signaling as well as activity of the enteric nervous system through the vagal nerve. That means that what happens in the gut has significant downstream impact related to neurotransmitters and can then influence mood, sleep, appetite, even pain sensation. And certain microbial metabolites like SCFAs can stimulate the release of serotonin from the ECCs. So our gut microbes do have direct influence on neurotransmitters.

95% of the body’s serotonin is produced and stored in something called enteroendocrine and enterochromaffin cells or ECCs. These ECCs are integral in modulation of brain signaling as well as activity of the enteric nervous system through the vagal nerve. That means that what happens in the gut has significant downstream impact related to neurotransmitters and can then influence mood, sleep, appetite, even pain sensation. And certain microbial metabolites like SCFAs can stimulate the release of serotonin from the ECCs. So our gut microbes do have direct influence on neurotransmitters.

Using Food as Medicine Via Micronutrients

Our body processes (digests and absorbs) and synthesizes nutrients but not in isolation. Just like the food our clients ingest don’t contain just 1 or 2 micronutrients. They contain vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and essential fats that not only are broken down directly by the body but also utilized by our microbiome or used as cofactors for enzyme processes.

Our body processes (digests and absorbs) and synthesizes nutrients but not in isolation. Just like the food our clients ingest don’t contain just 1 or 2 micronutrients. They contain vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and essential fats that not only are broken down directly by the body but also utilized by our microbiome or used as cofactors for enzyme processes.

With that said, there have been studies on the roles of specific nutrients as related to health, both physical and mental. Nutrients like B vitamins, folate, omega-3 fats, and zinc influence brain development and function. Therefore deficiencies can create issues with neurotransmitters, mood, cognition, and even the development of brain disorders.

A well-rounded, bioindividual diet looking at the person’s current circumstances provides the best approach to give their body what it needs to thrive.

A Future Built on Personalized Nutrition for Mental Health

As we look at ongoing research on the role of nutrition, it becomes clearer with each study that the impact and power of the right therapeutic diet approach for your clients can make a world of difference, not just in their physical health but their mental health as well. So much in fact that more integrative mental health professionals should be looking to nutrition as a front-line intervention, a key point Horn et al. make in their research study.

Assessing current nutrition, microbiome status, individual food intolerances or issues with food compounds like FODMAPs, oxalates, polysaccharides, or salicylates, and creating a personalized nutrition plan that nourishes the body, microbiome, and brain helps our clients heal and thrive.

This process is the basis for my BioIndividual Nutrition Institute and what I teach to the health professionals leading this charge of personalized, bioindividual nutrition for health and wellbeing. The potential to make a difference in the mental health crisis our country – and the world at large – is facing is incredible.

If you want to take your practice to the next level, I encourage you to explore my training programs, there are two – a BioIndividual Nutrition Training foundations program and a Pediatric Program which includes the foundational training as well as a pediatric intensive course to prepare you to support the pediatric population including children with ADHD, autism, and other neurological disorders. Now, more than ever, the world needs you.

Reference

- Horn J, Mayer DE, Chen S, Mayer EA. Role of diet and its effects on the gut microbiome in the pathophysiology of mental disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):164. Published 2022 Apr 20. doi:10.1038/s41398-022-01922-0

- Bush, C. L., Blumberg, J. B., El-Sohemy, A., Minich, D. M., Ordovás, J. M., Reed, D. G., & Behm, V. A. Y. (2019). Toward the Definition of Personalized Nutrition: A Proposal by The American Nutrition Association. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 1-11.

- Kordas K, Lonnerdal B, Stoltzfus RJ. Interactions between nutrition and environmental exposures: effects on health outcomes in women and children. The Journal of nutrition. 2007 Dec 1;137(12):2794-7.

- Ferguson LR, De Caterina R, Görman U, Allayee H, Kohlmeier M, Prasad C, Choi MS, Curi R, De Luis DA, Gil Á, Kang JX. Guide and position of the international society of nutrigenetics/nutrigenomics on personalised nutrition: part 1-fields of precision nutrition. Lifestyle Genomics. 2016;9(1):12-27.

- Rubio-Aliaga I, Kochhar S, Silva-Zolezzi I. Biomarkers of nutrient bioactivity and efficacy: a route toward personalized nutrition. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2012 Aug 1;46(7):545-54.