When it comes to emerging treatments to address symptoms of autism, few things have garnered the attention (or Google searches) as the fecal transplant. This treatment gained the spotlight in early 2019 after researchers in Tempe and Flagstaff, AZ completed the first clinical trial with very positive results.

Fecal transplants stand on the cutting edge of autism innovation. Recent research highlights these transplants as a treatment for autism spectrum disorder — one that has huge potential. If you’re familiar with autism or my work, you may be aware that gut health can affect autism symptoms, from repetitive behaviors to social interaction.

In the past few years, science has begun to catch up to the idea that the microbiome matters for nearly every facet of health. The microbiome is the unique combination of organisms that live in your body. These microscopic building blocks are specifically concentrated in the intestines.

An excellent microbiome can “prevent disease and optimize health.” For people with autism, the issue is of vital importance, since autism is associated with distinct, severe gut problems and microbiome deficiencies. So, how can we improve the microbiome and expand the good bacteria in the body?

New research is showing that an answer may be found in a total reset of gut bacteria by using the extensive microbiome of a healthy gut, this can be accomplished by a new medical procedure called a fecal transplant. Fecal transplants have, so far, been used with differing levels of success to treat recurrent C. difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and even Alzheimer’s.

While there’s not enough research yet to make this a widely practiced treatment, it’s worth our attention. Read on for the practice, potential, and pitfalls of this emerging treatment of fecal transplant for autism.

What is a fecal transplant?

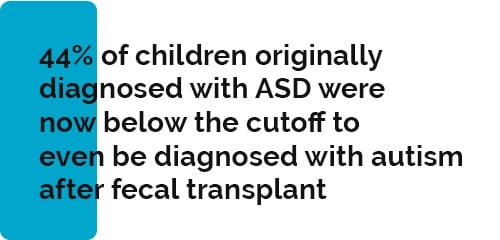

Typically, we hear the word “transplant” associated with organs and tissue, but a transplant can refer to moving any specimen from one location to another. This is exactly what happens in a typical fecal transplant — extremely healthy, screened feces is transplanted into the colon of the recipient. This process is also referred to as microbiota transfer therapy (MTT).

This idea was first brought into the arena by Dr. Thomas Borody, an Australian gastroenterologist looking for ways to improve the gut health of his patients. As a doctor specializing in GI problems, he noticed that repopulating the bacteria in the digestive tract could benefit his patients long-term. In fact, he noticed that roughly 90% of patients being treated for recurring digestive diseases saw improvement after the procedure. Now, the ripple effect of this transplant is being studied for other conditions, like ASD.

While a traditional fecal transplant involves implanting a stool sample through a colonoscopy, other ways are emerging to achieve the same benefits. Fecal microbiota transplantation doesn’t have to be a rectal insertion. Truly, any maneuver that allows healthy microbiota to get into the digestive tract can be effective. One study I discuss later in the article involves the purification of waste matter down to just the bacteria, and then provided this concoction of gut microbes, orally.

This procedure is more effective than an over-the-counter probiotic due to its high diversity and potency, as well as its method of delivery. However, the bowel cleanse required before the procedure is also very helpful, as it provides something akin to a clean slate. In their new home, these beneficial bacteria can begin to improve both the gut-brain axis and autism-related symptoms of the individual. A fecal transplant for autism holds incredible potential.

Autism and Gut Microbiome Problems

Autism is generally known for its neurological symptoms: impairments in behavior, communication, and social skills. As such, most treatments until now have focused on behavior modification, speech therapy, or medication.

However, at Nourishing Hope, we know good nutrition puts hope into action. In extensive research, including the paper I participated in, we’ve effectively proven how much diet can affect autism symptoms (improvements in gastrointestinal function and behavior), and this fecal transplant fits right into our gut-centered theory and nutritional strategies.

Why would this highly unusual procedure be necessary? Clinical trials and research alike increasingly show that gut microbiota have a strong connection to both brain development and behavioral symptoms. The greater microbial diversity, the better the odds of a healthy gut. Adding in the gut microbes of a healthier person diversifies the good bacteria, improving social, behavioral, and communication symptoms of ASD.

Unfortunately, children with autism are generally plagued by gastrointestinal symptoms. This is partially due to their unusual microbiomes, with higher ratios of “bad” bacteria than other patients, and lower percentages of “good” bacteria like Bifidobacterium. This lack of microbial diversity, along with disproportionate rates of harmful microbiota, affects everything from the immune system to neurological health.

In fact, just one bacteria, Prevotella, is commonly lacking in autistic patients. As it turns out, lack of Prevotella is linked to autism-like symptoms. The researchers in this study found that a lack of diversity in the gut influenced symptoms of autism (interestingly, separate from their individual diet, although they did point out the presence of “unusual diet patterns” in the subjects).

This Prevotella study shows that microbiome diversity is a major key to addressing autism symptoms. The connection between the gut and autism is undeniable. The question has been: how can we correct these gut issues to resolve symptoms?

New research in this field may offer one of the first solid answers to this question.

Current Research on Fecal Transplant for Autism

Aware of the major breakthroughs being made in Australia with these transplants, an American team decided to apply them to an issue close to home. Dr. James Adams (my mentor), Dr. Rosa Krajmalnik-Brown, and a team of Arizona State University and Northern Arizona University researchers pursued a more palatable way to perform a fecal transplant for autism.

The results were far beyond what they were looking for as an outcome of their groundbreaking new open-label trial.

The team at the Biodesign Institute was aware of the rising epidemic of an autism diagnosis. The CDC has estimated that more than one in every 59 children now has ASD. Knowing this link between the potential therapeutic role that a healed gut microbiome can play and the severity of ASD symptoms, they innovated a new angle on a fecal transplant for autism.

Researchers from the Swette Center for Environmental Biotechnology took the feces of a screened, extremely healthy donor pool. From these samples, they purified out the waste matter. This left the “super probiotics,” or the gut bacteria found in these healthy specimen’s microbiome. Their theory was that this diverse, healthy microbiome sampling would improve not only the childrens’ GI symptoms, but their ASD symptoms as well.

First, the children were prescribed vancomycin, an antibiotic to cleanse the gut microbiome. This was meant to knock out Clostridium difficile (C. diff) and any other “bad bacteria” existing in the intestinal tract. This assists in the goal to raise the level of beneficial bacteria, since it removes the microbiota that might attack any beneficial bacteria. Next came a bowel cleanse and a half-day fast, then the transplant could begin safely.

They began taking this probiotic orally in high doses for two days, and lower doses for eight more weeks. A stomach acid suppressant was also used, boosting the new bacteria’s chance of surviving. Each clinical trial participant had their microbiomes tested over these eight weeks, and the results were astounding.

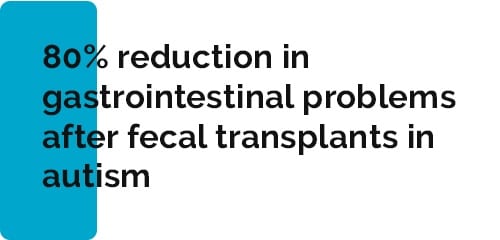

By week five, the scientists saw an 80% reduction in gastrointestinal problems. By week eight, there was a 25% reduction in overall symptoms of ASD. And the benefits continued over two years, and counting.

These kind of results are extremely rare in autism intervention and study! The benefits seemed to last throughout the trial, and preliminary results pointed to a fecal transplant for autism as a real solution.

Recently, the team at ASU conducted a two year follow-up study, published in early 2019. Surprisingly, this demonstrated that the benefits of the transplant are still in effect. More than just continuing far past the expected impact, the children’s microbiomes are even more diverse than at the end of the trial. This potential treatment is a rare breed: one that seems to show even more significant improvements as time passes, and continues benefits after intervention has ended.

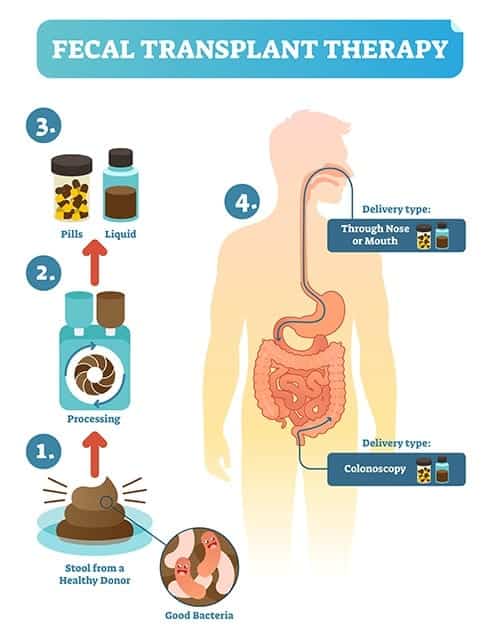

Other proposed therapies in the past have included antibiotics, but benefits end shortly post-treatment. On the other hand, this could have lasting, positive effects on recipients’ overall symptoms and health. A professional evaluator at the two year follow-up found that subjects showed a 45% decrease in core ASD symptoms.

In a startlingly good outcome, 44% of children originally diagnosed with ASD were now below the cutoff to even be diagnosed with autism. This sounds like “autism recovery” to me. This is tremendous news! The improvement in GI symptoms, behavioral and social symptoms, and gut microbiota is a holistic solution to many of the gastrointestinal woes children with autism face.

Areas of Future Study

While the initial findings of this team are promising, further clinical trials are needed to plug certain holes in the current research. The sample size of 18 children is small, and by no means conclusive or applicable to everyone. We would need a much greater number of successful efforts to vet and successfully reproduce the results of this trial.

Excitingly, the researchers are embarking on a larger, placebo-controlled trial of this fecal transplant for autism in adults. We also aren’t yet sure how these procedures affect adults, since only children participated in the first trial.

Furthermore, for more well-rounded scientific reports, it would be excellent to include double-blind studies. Removing researchers’ bias will help provide a more unbiased report. There is always a potential for the placebo effect unless double-blinded studies are used. This term refers to the bias in participants that something is changing simply because they’re participating in the trial.

It may be several years before sufficient research has been published to gain FDA approval for fecal transplant for autism. However, in May 2019, the FDA did give this treatment “fast track status,” meaning it will receive priority in approvals. At the moment, this procedure isn’t performed outside of research settings for this particular condition.

It also remains to be seen exactly how fecal transplant for autism will differ from the development of probiotics. To date, research on fecal transplant therapy displays a much higher efficacy for this therapy as opposed to generalized probiotics. Theories for this are limited, but I think it’s because there are many more strains of bacteria in stool, not to mention other microbes (beneficial viruses, etc.) that likely affect the diversity of the microbiome.

The isolated microbiome of a healthy host in fecal transplant for autism is also different than, say, fecal transplant for C. diff infection. The individualized biome markers used to treat one condition don’t extend to the next condition — an additional reason why a probiotic with generalized bacterial strains is less effective (though may still be beneficial).

Dangers of Fecal Transplants

The FDA published a strong warning about fecal matter for transplantation (FMT) on June 13, 2019. The warning elaborates on a lack of testing that occurred with a stool donation. Unfortunately, that stool was later tested and found to contain E. coli traces. And the effects were deadly for one immunocompromised recipient.

Of the two known subjects that received a transplant from the infected donor, one died and the other became extremely ill. This poses an extra level of concern since most patients receiving FMT are not in top immune condition, even if they aren’t immunocompromised. Clearly, standardized and thorough testing should be a top priority before administering a fecal transplant for autism or other purposes.

It’s worth noting, however, that no major medical procedure exists without some reasonable risks that may occur in a very small number of cases.

In light of this development, there are FDA concerns that must be met before it becomes an FDA-approved treatment. Firstly, there is a call for stool donations and donors to be tested for MDROs (drug-resistant bacteria)– such as MRSA, VRE, and resistant Acinetobacter. These typically resist antibiotics and other attempts to medicate, and can be deadly to patients with an already-weak microbiome.

The FDA also urges doctors to openly discuss the risks of this procedure and the investigational nature of fecal transplants. Properly informing and receiving consent from patients is key. Finally, guidelines were recently published about how and how often to screen donations for MDROs.

Clearly, until these potentially fatal flaws can be worked out of a fecal transplant for autism, it won’t be widely administered. However, as research and standards move forward, its chances improve. Until then, it’s not widely available outside clinical trials.

Summary

- Fecal transplants (microbiota transfer therapy or FMT) hold great promise for the future of autism treatment.

- Unlike most treatments, the positive effects of FMT are long-lasting, increase over time, and have exceptional success in treating ASD core behaviors.

- A fecal matter transplant gets at the microbiome issues that ASD patients can suffer from, helping with digestive discomfort as it diversifies the microbiome.

- While the research is highly promising, larger-scale studies, double-blind participation, and adult patients are needed for a rounded approach.

- Unfortunately, fecal matter transplants aren’t yet widely available in the U.S., but progress is being made toward FDA approval.

In Conclusion

This helps us to see how powerful and important the microbiome is in autism, and how improving the microbiome can improve symptoms, in cases leading autism recovery. Though it may not compare or replace FMT, while we await further study on fecal transplant, it seems prudent to use the food strategies we know that may be able to positively improve the microbiome. Strategies such as: fermented foods and probiotics, and foods that support the growth of good bacteria like prebiotic foods have been used by nutritionists and functional medicine practitioners for decades.

Parents should be enthused by the research and scientific vigor of today. Hope continues.

Sources

- Mayer, E. A., Padua, D., & Tillisch, K. (2014). Altered brain‐gut axis in autism: Comorbidity or causative mechanisms?. Bioessays, 36(10), 933-939. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25145752

- Hollister, E. B., Gao, C., & Versalovic, J. (2014). Compositional and functional features of the gastrointestinal microbiome and their effects on human health. Gastroenterology, 146(6), 1449-1458. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4181834/

- Bakken, J. S., Borody, T., Brandt, L. J., Brill, J. V., Demarco, D. C., Franzos, M. A., … & Moore, T. A. (2011). Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 9(12), 1044-1049. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3223289/

- Cryan, J. F., & O’mahony, S. M. (2011). The microbiome‐gut‐brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 23(3), 187-192. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21303428

- Vuong, H. E., & Hsiao, E. Y. (2017). Emerging roles for the gut microbiome in autism spectrum disorder. Biological psychiatry, 81(5), 411-423. Abstarct: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27773355

- Horvath, K., & Perman, J. A. (2002). Autism and gastrointestinal symptoms. Current gastroenterology reports, 4(3), 251-258. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12010627

- MacFabe, D. (2013). Autism: metabolism, mitochondria, and the microbiome. Global advances in health and medicine, 2(6), 52-66. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3865378/

- Williams, B. L., Hornig, M., Parekh, T., & Lipkin, W. I. (2012). Application of novel PCR-based methods for detection, quantitation, and phylogenetic characterization of Sutterella species in intestinal biopsy samples from children with autism and gastrointestinal disturbances. MBio, 3(1), e00261-11. Abstract: https://pubag.nal.usda.gov/catalog/130227

- De Angelis, M., Piccolo, M., Vannini, L., Siragusa, S., De Giacomo, A., Serrazzanetti, D. I., … & Francavilla, R. (2013). Fecal microbiota and metabolome of children with autism and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. PloS one, 8(10), e76993. Full text: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0076993

- Kang, D. W., Park, J. G., Ilhan, Z. E., Wallstrom, G., LaBaer, J., Adams, J. B., & Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2013). Reduced incidence of Prevotella and other fermenters in intestinal microflora of autistic children. PloS one, 8(7), e68322. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3700858/

- Kang, D. W., Adams, J. B., Gregory, A. C., Borody, T., Chittick, L., Fasano, A., … & Pollard, E. L. (2017). Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome, 5(1), 10. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5264285/

- Li, Q., & Zhou, J. M. (2016). The microbiota–gut–brain axis and its potential therapeutic role in autism spectrum disorder. Neuroscience, 324, 131-139. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26964681

- Kang, D. W., Adams, J. B., Coleman, D. M., Pollard, E. L., Maldonado, J., McDonough-Means, S., … & Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2019). Long-term benefit of Microbiota Transfer Therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Scientific reports, 9(1), 5821. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6456593/

- Rosenfeld, C. S. (2015). Microbiome disturbances and autism spectrum disorders. Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 43(10), 1557-1571. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25852213

- Khoruts, A. (2018). Targeting the microbiome: from probiotics to fecal microbiota transplantation. Genome medicine, 10(1), 80. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6208019/